The rate of change of mass in \(V\) is

\begin{equation*}

\dd{}{t} \iiint_V \rho(\bx, t) \, \de V = \iiint_V \pd{\rho}{t} \, \de V,

\end{equation*}

and note the derivative passes through the integral since the volume, \(V\text{,}\) does not change with time.

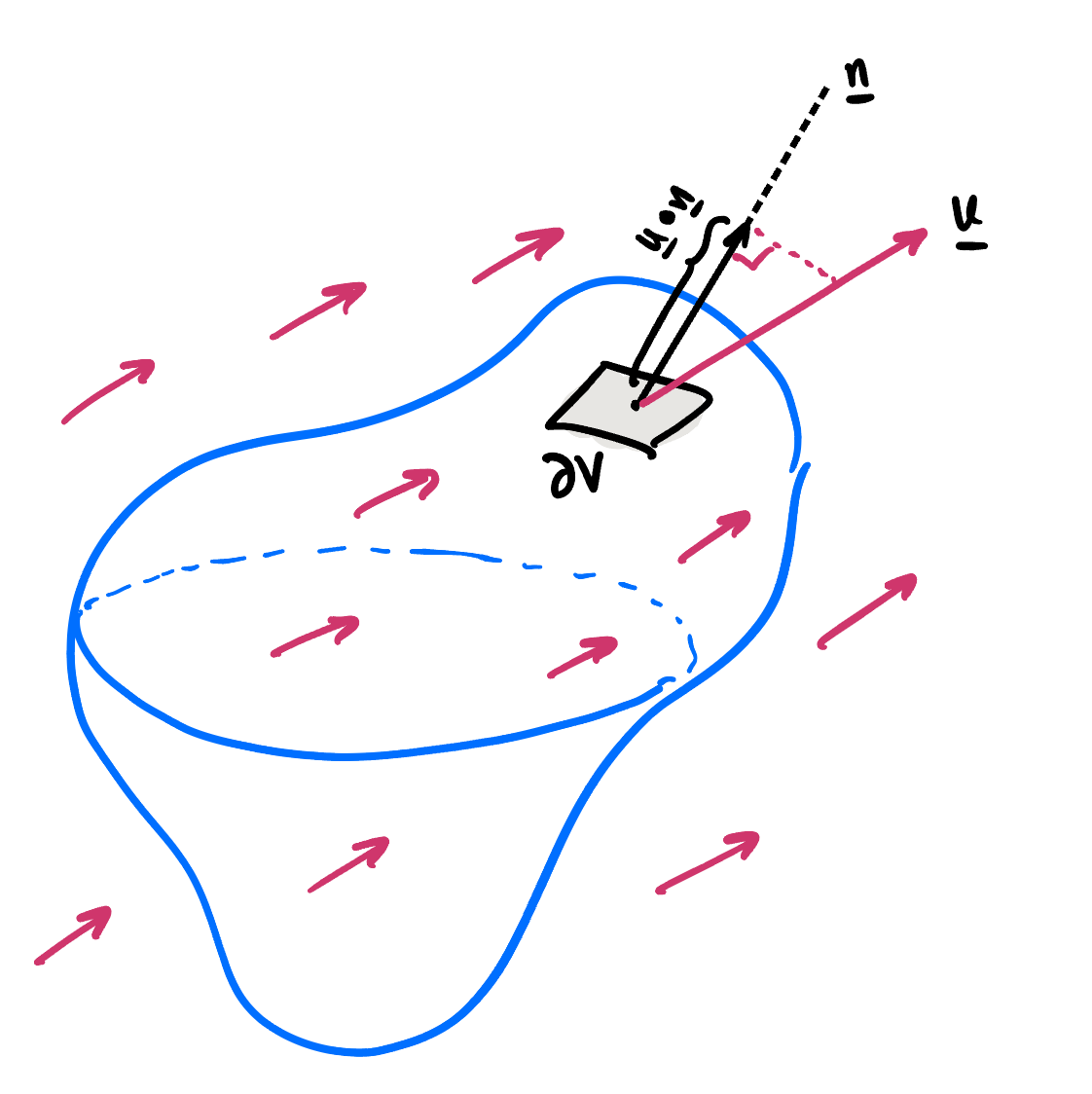

Let the boundary of

\(V\) be given by

\(\partial V\text{,}\) and let

\(\bn\) denote the outward unit normal defined along the boundary

\(\partial V\text{.}\) At each point on the boundary, the volume flow rate (known as the

flux) across the boundary is given by

\(\bu

\cdot \bn\) and therefore the mass flow rate is

\(\rho \bu \cdot \bn\text{.}\)

We now sum the total mass flow across the entire boundary. This is given by the surface integral

\begin{equation*}

\text{rate of mass change across $\partial V$} = \iint_{\partial V} \rho \bu \cdot \bn

\,

\de{S}.

\end{equation*}

The flux out of the boundary is also sketched in

Figure 3.2.3.

Mass conservation is now applied. Therefore, the rate of change of pass in the volume

\(V\) is equal to the rate at which mass enters the boundary in the

inwards direction.