Proof of the first vortex theorem. For a given vortex line, choose two vortex surfaces containing the line such that the vortex line is the intersection of the two vortex surfaces.

Choose a closed curve \(C\) lying within one the vortex surfaces. The circulation around \(C\) is

\begin{equation*}

\Gamma=\oint_C\bu\cdot\de\bx=\iint_S\bomega\cdot\bn\,\de S,

\end{equation*}

where the final equality is by Stokes’ theorem. Since the curve is within the vortex surface, the vorticity is parallel to the surface, and hence

\(\bomega\cdot\bn=0\text{.}\) Thus

\(\Gamma=0\text{,}\) and by Kelvin’s circulation theorem

Theorem 6.1.2,

\(\Gamma\) must remain at zero for all times.

Thus at time

\(t\text{,}\) the evolved surface has circulation zero for all closed curves, and therefore by Stokes’ theorem, the integral of

\(\bomega\cdot\bn\) over any sub-surface must be zero. Hence

\(\bomega\cdot\bn=0\) at all points on the surface, meaning that the vorticity is everywhere parallel to the evolved surface. This means that the evolved surface must be a vortex surface.

Recall that any vortex line can be defined by the intersection of two vortex surfaces. Let the two surfaces evolve and the evolution of the vortex line remains as the intersection of the two evolved vortex surfaces. As proven already, the vorticity is everywhere parallel to the two evolved vortex surfaces and thus it is parallel to the evolved vortex line. This means that it remains as a vortex line.

This completes the proof of the first vortex theorem: vortex lines evolve with the fluid. We sometimes say that the vortex lines are `frozen’ in the fluid, meaning that the evolve in the same way as a dye `frozen’ into the fluid would.

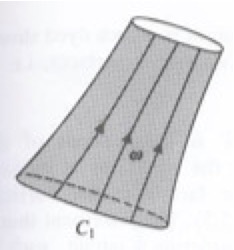

Proof of the second vortex theorem. Proof that \(\Gamma\) is the same for all cross-sections. To prove the second vortex theorem, choose two different cross-sections of the vortex tube, \(S_1\) and \(S_2\) say, and consider the section \(V\) of the vortex tube lying between \(S_1\) and \(S_2\text{.}\) We integrate over the surface of \(V\text{:}\)

\begin{equation*}

\iint_{\partial V}\bomega\cdot\bn\de S

=\iint_{S_2}\bomega\cdot\bn\de S

-\iint_{S_1}\bomega\cdot\bn\de S

+\iint_{\mathrm{outside}}\bomega\cdot\bn\de S,

\end{equation*}

where `outside’ refers to the outer surface of the vortex tube between \(S_1\) and \(S_2\text{.}\) Since vortex lines are paralled to this surface, we have \(\bomega\cdot\bn=0\) there, and so

\begin{equation*}

\iint_{\partial V}\bomega\cdot\bn\de S

=\iint_{S_2}\bomega\cdot\bn\de S

-\iint_{S_1}\bomega\cdot\bn\de S.

\end{equation*}

Now, by the divergence theorem,

\begin{equation*}

\iint_{\partial V}\bomega\cdot\bn\de S

=\iiint_V\nabla\cdot\omega \de V,

\end{equation*}

but this equals zero, since \(\nabla\cdot\omega=0\) (divergence of a curl is zero).

Putting this together,

\begin{equation*}

\iint_{\partial V}\bomega\cdot\bn\de S

=\iint_{S_2}\bomega\cdot\bn\de S

-\iint_{S_1}\bomega\cdot\bn\de S

=0.

\end{equation*}

and this was true for any choice of \(S_1\) and \(S_2\text{.}\) Hence, \(\Gamma\) is the same for all cross-sections of a vortex tube.

Proof of the second vortex theorem (continued). Proof that \(\Gamma\) is independent of time. To prove that

\(\Gamma\) is independent of time, we note that, since the vortex lines move with the fluid, the vortex tube also moves with the fluid, being composed of vortex lines, and the same vortex lines lie on the surface and are enclosed within the vortex tube for all time.

Moreover,

\begin{equation*}

\Gamma=\iint\omega\cdot\bn\de S

=\oint\bu\cdot\de\bx

\end{equation*}

by Stokes’ theorem, which is the circulation around the boundary of

\(S\text{.}\) As the tube evolves, the material surface

\(S\) moves with the vortex tube. By Kelvin’s circulation theorem

Theorem 6.1.2,

\(\Gamma\) remains independent of

\(t\text{.}\)