We note that \(\iiint_{V(t)} \rho\bu \, \de{x} \, \de{y} \, \de{z}\) is the integral of the linear momentum per unit volume over the volume and is therefore the total momentum of the fluid particles in \(V(t)\text{.}\) The left-hand side of this equation is thus the Lagrangian rate of change of momentum of these fluid particles. By Newton’s second law, this must equal the resultant force acting on the fluid in \(V(t)\text{,}\) which we denote by \(\bF\text{.}\) This force is the sum of different contributions, which can be categorised into body forces (which act on the whole volume of fluid) and surface forces (acting only on the surface of the fluid, and which arise from the fluid stress):

\begin{equation*}

\dd{}{t} \iiint_{V(t)} \rho\bu \, \de{x} \, \de{y} \, \de{z}

= \bF

= \bF_{\textrm{body}} + \bF_{\textrm{surface}}.

\end{equation*}

Body forces: In this course, these are equal to either zero (if gravity is not important) or equal to the gravitational force

\begin{equation*}

\bF_{\textrm{surface}}=\bF_{\textrm{gravity}}=\rho V\bg.

\end{equation*}

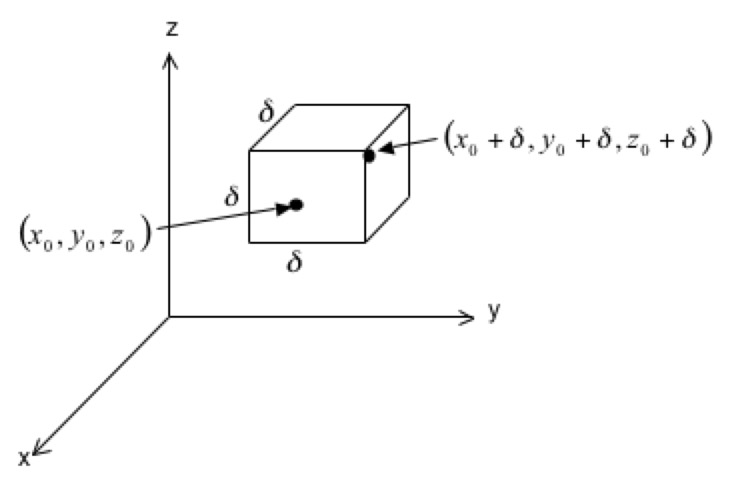

Surface forces: These arise from the stress exerted at the surface of the fluid parcel, and these can be computed by integrating the stress vector

\(\tau\) over the surface of the cube. On the left face, we have

\(\bn=-\bi\text{,}\) and, using

(7.4.5), the stress vector is

\begin{align*}

\btau=&\bsigma\bn\\

=&\left(-p\bI+2\mu\be\right)\left(-\bi\right)\\

=&\left(\begin{matrix}

-p+2\mu\pd{u}{x}&\mu\left(\pd{u}{y}+\pd{v}{x}\right)&\mu\left(\pd{u}{z}+\pd{w}{x}\right)\\

\mu\left(\pd{u}{y}+\pd{v}{x}\right)&-p+2\mu\pd{v}{y}&\mu\left(\pd{v}{z}+\pd{w}{y}\right)\\

\mu\left(\pd{u}{z}+\pd{w}{x}\right)&\mu\left(\pd{v}{z}+\pd{w}{y}\right)&-p+2\mu\pd{w}{z}

\end{matrix}\right)

\left(\begin{matrix}-1\\0\\0\end{matrix}\right)\\

=&-\left(\begin{matrix}

-p+2\mu\pd{u}{x}\\

\mu\left(\pd{u}{y}+\pd{v}{x}\right)\\

\mu\left(\pd{u}{z}+\pd{w}{x}\right)

\end{matrix}\right),

\end{align*}

and the force on the left face is this expression multiplied by the area \(\delta^2\text{.}\) Similarly, on the right-hand face, we have \(\bn=\bi\text{,}\) and the stress vector is

\begin{equation*}

\btau=\bsigma\bn

=\left(\begin{matrix}

-p+2\mu\pd{u}{x}\\

\mu\left(\pd{u}{y}+\pd{v}{x}\right)\\

\mu\left(\pd{u}{z}+\pd{w}{x}\right)

\end{matrix}\right),

\end{equation*}

with the contribution to the force being this expression multiplied by \(\delta^2\text{.}\) Hence the contribution to the force from the left and right faces is

\begin{align*}

&\left.\left(\begin{matrix}

-p+2\mu\pd{u}{x}\\

\mu\left(\pd{u}{y}+\pd{v}{x}\right)\\

\mu\left(\pd{u}{z}+\pd{w}{x}\right)

\end{matrix}\right)\delta^2\right|_{x=x_0+\delta}

-\left.\left(\begin{matrix}

-p+2\mu\pd{u}{x}\\

\mu\left(\pd{u}{y}+\pd{v}{x}\right)\\

\mu\left(\pd{u}{z}+\pd{w}{x}\right)

\end{matrix}\right)\delta^2\right|_{x=x_0}\\

=&\pd{}{x}\left(\begin{matrix}

-p+2\mu\pd{u}{x}\\

\mu\left(\pd{u}{y}+\pd{v}{x}\right)\\

\mu\left(\pd{u}{z}+\pd{w}{x}\right)

\end{matrix}\right)\delta^3\\

=&\pd{}{x}\left(\begin{matrix}

-p+2\mu\pd{u}{x}\\

\mu\left(\pd{u}{y}+\pd{v}{x}\right)\\

\mu\left(\pd{u}{z}+\pd{w}{x}\right)

\end{matrix}\right)V.

\end{align*}

After a similar calculation, the contributions from the front and back faces can be shown to be

\begin{equation*}

\pd{}{y}\left(\begin{matrix}

\mu\left(\pd{v}{x}+\pd{u}{y}\right)\\

-p+2\mu\pd{v}{y}\\

\mu\left(\pd{v}{z}+\pd{w}{y}\right)

\end{matrix}\right)V,

\end{equation*}

and from the top and bottom faces we get

\begin{equation*}

\pd{}{z}\left(\begin{matrix}

\mu\left(\pd{w}{x}+\pd{u}{z}\right)\\

\mu\left(\pd{w}{y}+\pd{v}{z}\right)\\

-p+2\mu\pd{w}{z}

\end{matrix}\right)V.

\end{equation*}

Hence the total force due to surface stresses is

\begin{align*}

\bF_{\textrm{surface}}=\bF_{\textrm{stress}}=&

\pd{}{x}\left(\begin{matrix}

-p+2\mu\pd{u}{x}\\

\mu\left(\pd{u}{y}+\pd{v}{x}\right)\\

\mu\left(\pd{u}{z}+\pd{w}{x}\right)

\end{matrix}\right)V

+\pd{}{y}\left(\begin{matrix}

\mu\left(\pd{v}{x}+\pd{u}{y}\right)\\

-p+2\mu\pd{v}{y}\\

\mu\left(\pd{v}{z}+\pd{w}{y}\right)

\end{matrix}\right)V

+\pd{}{z}\left(\begin{matrix}

\mu\left(\pd{w}{x}+\pd{u}{z}\right)\\

\mu\left(\pd{w}{y}+\pd{v}{z}\right)\\

-p+2\mu\pd{w}{z}

\end{matrix}\right)V\\

=&

\left(\begin{matrix}

-\pd{p}{x}+\mu\left(\pd{^2u}{x^2}+\pd{^2v}{x\partial y}+\pd{^2w}{x\partial z}+\nabla^2u\right)\\

-\pd{p}{y}+\mu\left(\pd{^2u}{x\partial y}+\pd{^2v}{y^2}+\pd{^2w}{y\partial z}+\nabla^2v\right)\\

-\pd{p}{z}+\mu\left(\pd{^2u}{x\partial z}+\pd{^2v}{y\partial z}+\pd{^2w}{z^2}+\nabla^2w\right)

\end{matrix}\right)V\\

=&\left(-\nabla p+\mu\left(\nabla\pd{u}{x}+\nabla\pd{v}{y}+\nabla\pd{w}{z}\right)

+\mu\nabla^2\bu\right)V\\

=&\left(-\nabla p+\mu\nabla\nabla\cdot\bu+\mu\nabla^2\bu\right)V\\

=&\left(-\nabla p+\mu\nabla^2\bu\right)V,

\end{align*}

where the final equality was obtained using the incompressibility condition

\(\nabla\cdot\bu=0\) (3.4.2).

Hence, the left-hand side of the Reynolds Transport Theorem becomes

\begin{equation*}

\dd{}{t} \iiint_{V(t)} \rho\bu \, \de{x} \, \de{y} \, \de{z}

= \bF_{\textrm{body}} + \bF_{\textrm{surface}}

= \left(\rho\bg-\nabla p + \mu\nabla^2\bu\right)V.

\end{equation*}