1. Kelvin’s Circulation Theorem.

The circulation \(\Gamma\) around a closed curve \(C(t)\) is defined by

\begin{equation*}

\Gamma = \oint_{C} \mathbf{u} \cdot \de\mathbf{x}.

\end{equation*}

By transforming to Lagrangian variables show that \(\Gamma\) is independent of \(t\text{.}\) Deduce that a flow that is initially irrotational (i.e. \(\bomega = 0\) at \(t=0\)) remains irrotational for all time.

Note that this is a key result: if a flow is initially irrotational, it remains so indefinitely and we can introduce a velocity potential \(\phi\) such that \(\mathbf{u} = \nabla \phi\text{.}\)

Hint.

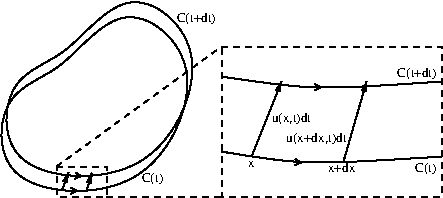

Method one: Consider the following diagram.

By definition,

\begin{equation}

\dd{\Gamma}{t}=\lim_{\de t\rightarrow0}\frac1{\de t}\left(\oint_{C(t+\de t)}\bu\cdot\de\bx-\oint_{C(t)}\bu\cdot\de\bx\right).\tag{6.5.1}

\end{equation}

We therefore need to write \(\bu\) and \(\de\bx\) at time \(t+\de t\) on the curve \(C(t+\de t)\) to values at time \(t\) on the curve \(C(t)\text{:}\)

\begin{align*}

&\left.\bu\cdot\de\bx\right|_{t+\de t}\\

=&\bu(\bx+\bu(\bx,t)\de t,t+\de t)\cdot\\

&\left((\bx+\de\bx+\bu(\bx+\de\bx,t)\de t)-(\bx+\bu(\bx,t)\de t)\right).

\end{align*}

Method two: We can parametrise \(C(t)\) via \(\bx(s,t)\) for \(0<s<1\) and rewrite the integral as an integral over the parameter \(s\text{:}\)

\begin{equation*}

\Gamma=\int_0^1\bu(\bx(s,t),t)\cdot\pd{\bx(s,t)}{s}\de s

\end{equation*}

Then start from (6.5.1) and simplify.

Solution.

We present two methods.

Method one:

Assuming a conservative body force \(-\bnabla\chi\) per unit volume, the Euler equation reads

\begin{equation*}

\DD{\bu}{t}=-\bnabla\left(\frac{p}{\rho}-\chi\right).

\end{equation*}

We have

\begin{equation*}

\dd{\Gamma}{t}=\lim_{\de t\rightarrow0}\frac1{\de t}\oint_C\left(\bu\cdot(\de\bx\cdot\bnabla)\bu-\bnabla\left(\frac{p}{\rho}-\chi\right)\cdot\de\bx\right)\de t.

\end{equation*}

We calculate

\begin{align*}

\left.\bu\cdot\de\bx\right|_{t+\de t}=&\bu(\bx+\bu(\bx,t)\de t,t+\de t)\cdot\\

&\left((\bx+\de\bx+\bu(\bx+\de\bx,t)\de t)-(\bx+\bu(\bx,t)\de t)\right)\\

=&\left(\bu(\bx,t)-\bnabla\left(\frac{p}{\rho}-\chi\right)\de t\right)\cdot\left(\de\bx+(\de\bx\cdot\bnabla)\bu\de t\right)\\

=&\left.\bu\cdot\de\bx\right|_{t}+\left(\bu\cdot(\de\bx\cdot\bnabla)\bu-\bnabla\left(\frac{p}{\rho}-\chi\right)\cdot\de\bx\right)\de t.

\end{align*}

Hence

\begin{align*}

\dd{\Gamma}{t}&=\lim_{\de t\rightarrow0}\frac1{\de t}\oint_C\left(\bu\cdot(\de\bx\cdot\bnabla)\bu-\bnabla\left(\frac{p}{\rho}-\chi\right)\cdot\de\bx\right)\de t\\

&=\oint_C\bu\cdot(\de\bx\cdot\bnabla)\bu-\bnabla\left(\frac{p}{\rho}-\chi\right)\cdot\de\bx\\

&=\oint_C\bnabla\left(\frac12\bu^2\right)\cdot\de\bx-\bnabla\left(\frac{p}{\rho}+\chi\right)\cdot\de\bx\\

&=\oint_C\bnabla\left(\frac12\bu^2-\frac{p}{\rho}-\chi\right)\cdot\de\bx\\

&=0.

\end{align*}

The final equality above follows because the line integral of a gradient around a closed curve is zero. Thus \(\Gamma\) is independent of \(t\text{.}\) If the flow is initially irrotational, then \(\Gamma=0\) at \(t=0\) for any closed curve \(C(0)\text{,}\) and hence \(\Gamma=0\) for all time. Since this holds for any closed curve, it follows that \(\omega=\bnabla\times\bu=0\) for all time.

Method two: This can also be proven by parametrising \(C(t)\) via \(\bx(s,t)\) for \(0<s<1\) and rewriting the integral as an integral over the parameter \(s\text{:}\)

\begin{equation*}

\Gamma=\int_0^1\bu(\bx(s,t),t)\cdot\pd{\bx(s,t)}{s}\de s.

\end{equation*}

Then

\begin{align*}

\dd{\Gamma}{t}=

&\int_0^1

\left.\pd{}{t}\left(\bu(\bx(s,t),t)\cdot\pd{\bx(s,t)}{s}\right)\right|_s\de s\\

=&\int_0^1

\left(\left(\pd{\bu}{t}+\pd{\bx}{t}\cdot\nabla\bu\right)\cdot\pd{\bx}{s}

+\bu\cdot\pd{^2\bx}{s\partial t}\right)\de s\\

=&\int_0^1

\left(\left(\pd{\bu}{t}+\bu\cdot\nabla\bu\right)\cdot\pd{\bx}{s}

+\bu\cdot\pd{\bu}{s}\right)\de s\\

=&\int_0^1\left(\DD{\bu}{t}\cdot\pd{\bx}{s}+\frac12\pd{|\bu|^2}{s}\right)\de s\\

=&\int_0^1\left(-\bnabla\left(\frac{p}{\rho}-\chi\right)\cdot\pd{\bx}{s}+\frac12\pd{|\bu|^2}{s}\right)\de s\\

=&\int_0^1\left(-\pd{}{s}\left(\frac{p}{\rho}-\chi\right)+\frac12\pd{|\bu|^2}{s}\right)\de s\\

=&0.

\end{align*}