Definition 7.4.2. Incompressible Newtonian fluid.

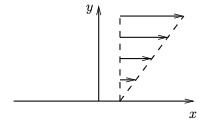

We can define a Newtonian fluid by stating its constitutive relationship.

\begin{equation}

\sigma_{ij}=-p\delta_{ij}

+\mu\left(\pd{u_j}{x_i}+\pd{u_i}{x_j}\right),\tag{7.4.1}

\end{equation}

where \(\mu\) is the dynamic shear viscosity. Alternatively, in vector form,

\begin{equation}

\bsigma=-p\bI+2\mu\be,\tag{7.4.2}

\end{equation}

where \(\be\) is the rate-of-strain tensor,

\begin{equation*}

\be=\left(\begin{matrix}

e_{11}&e_{12}&e_{13}\\

e_{21}&e_{22}&e_{23}\\

e_{31}&e_{32}&e_{33}

\end{matrix}\right),

\end{equation*}

where

\begin{equation}

\be=\frac12\left(\nabla\bu+\left(\nabla\bu\right)^T\right)

\quad\textrm{or}\quad

e_{ij}=\frac12\left(\pd{u_j}{x_i}+\pd{u_i}{x_j}\right),\tag{7.4.3}

\end{equation}

or, alternatively,

\begin{equation}

\be=\left(\begin{array}{ccc}

\pd{u}{x}&\frac12\left(\pd{u}{y}+\pd{v}{x}\right)&\frac12\left(\pd{u}{z}+\pd{w}{x}\right)\\

\frac12\left(\pd{u}{y}+\pd{v}{x}\right)&\pd{v}{y}&\frac12\left(\pd{v}{z}+\pd{w}{y}\right)\\

\frac12\left(\pd{u}{z}+\pd{w}{x}\right)&\frac12\left(\pd{v}{z}+\pd{w}{y}\right)&\pd{w}{z}

\end{array}\right).\tag{7.4.4}

\end{equation}

All three of these forms ((7.4.3) and (7.4.4)) are equivalent. Using (7.4.2), we may write the stress tensor of an incompressible Newtonian fluid in component form in Cartesian coordinates as

\begin{equation}

\bsigma=\left(\begin{matrix}

-p+2\mu\pd{u}{x}&\mu\left(\pd{u}{y}+\pd{v}{x}\right)&\mu\left(\pd{u}{z}+\pd{w}{x}\right)\\

\mu\left(\pd{u}{y}+\pd{v}{x}\right)&-p+2\mu\pd{v}{y}&\mu\left(\pd{v}{z}+\pd{w}{y}\right)\\

\mu\left(\pd{u}{z}+\pd{w}{x}\right)&\mu\left(\pd{v}{z}+\pd{w}{y}\right)&-p+2\mu\pd{w}{z}

\end{matrix}\right).\tag{7.4.5}

\end{equation}