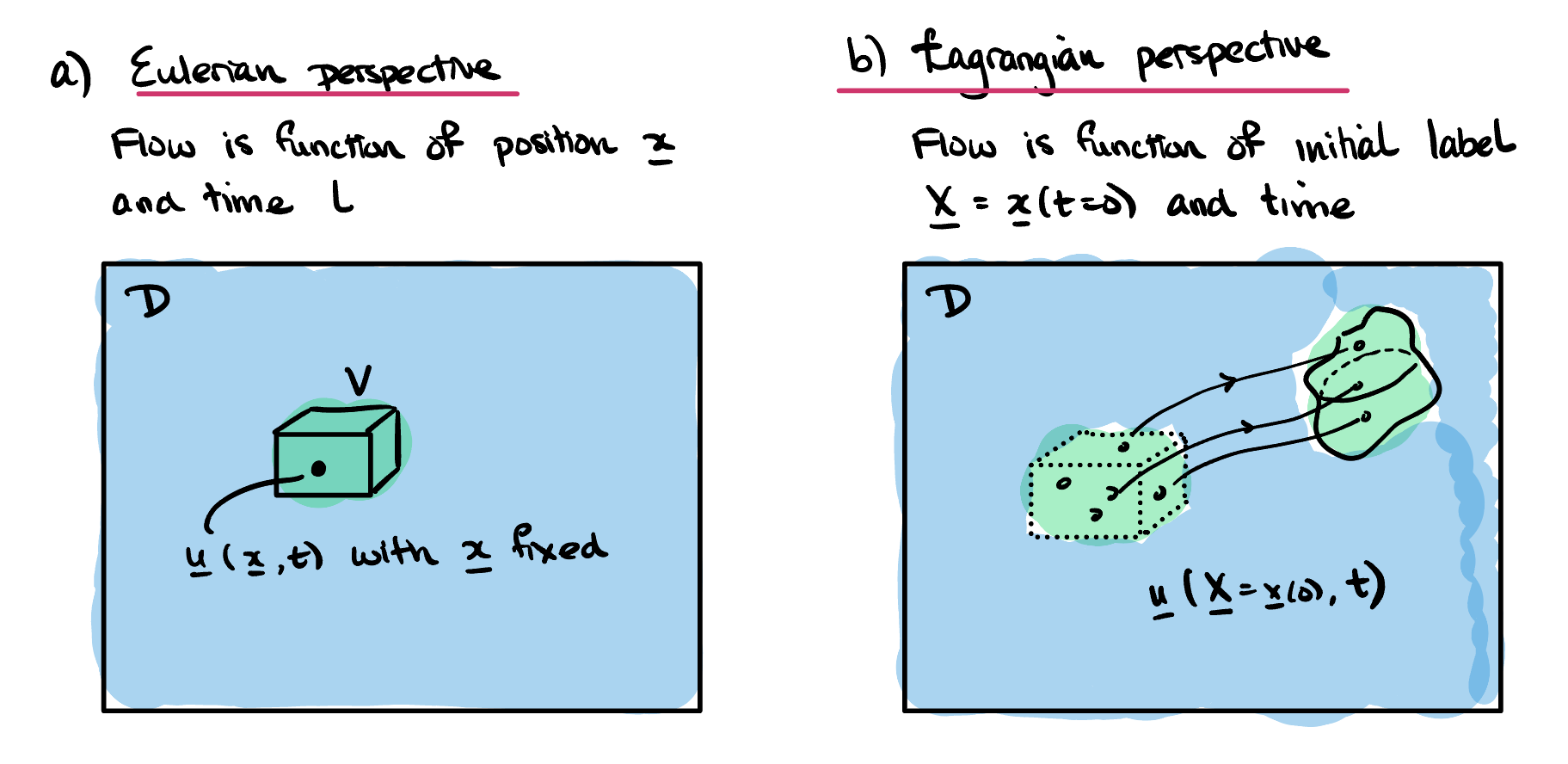

There are essentially two natural ways to think of motion in a fluid. We can imagine positioning ourselves at a fixed point in space,

\(\bx = (x, y, z)\text{.}\) At this point, we then attempt to measure a fluid quantity such as the density,

\(\rho(\bx, t)\text{,}\) or temperature,

\(T(\bx, t)\text{.}\) This is essentially the

Eulerian frame. One can imagine, for example, fixing sensor station into the ocean bottom, and obtaining measurements of the water temperature.

Alternatively, we can imagine tracking of a single fixed particle (or a fluid element) within the flow. The particle begins at some position. Let us define a label to describe the particle’s initial position. For example, if the particle’s position is given by

\begin{equation*}

(x, y, z) = (x_1(t), y_1(t), z_1(t)),

\end{equation*}

we can define the corresponding Lagrangian label as

\begin{equation*}

\bX = (X, Y, Z) = (x_1(0), y_1(0), z_1(0)).

\end{equation*}

We then ask for the corresponding measurement of the fluid quantity that corresponds to the label \(\bX\text{.}\) For example, this is equivalent to tagging a free-floating buoy in the ocean with the label \(\bX\text{,}\) then measuring the temperature of the water as the buoy drifts in the ocean. This Lagrangian temperature could be written \(\mathcal{T}(\bX, t),\) where \(\bX\) is simply a fixed quantity for the particular buoy.

Definition 2.1.2.

The Eulerian velocity

\(\bu(\bx,t)\) is the velocity of the fluid at the point with spatial coordinates

\(\bx\) at time

\(t\text{.}\) Note that, in physical terms this velocity is the average velocity at the time

\(t\) of the fluid particles (e.g. molecules, ions) in a small box centred on the point

\(\bx\text{.}\) See also

Remark 3.0.3 for a discussion of the continuum assumption.

Note that steady flow does not mean that the fluid particles are not moving. It simply means that at a fixed point in space, the Eulerian velocity does not change in time. The Lagrangian velocity of a fluid particle will generally change in time, even in a steady flow.