1. Continuum approximation.

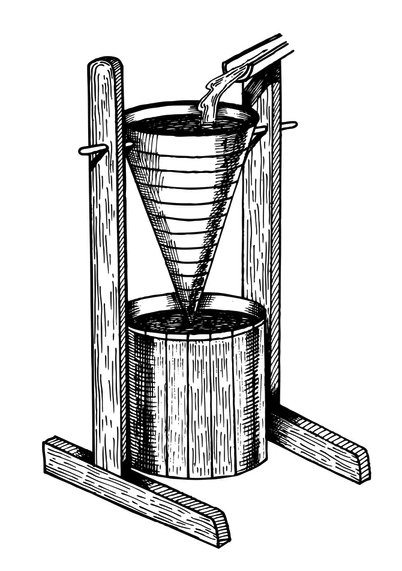

Domestic salt flows quite well out of a container with a hole in the bottom. Following Remark 3.0.3, consider whether salt matches up to the properties quoted for a fluid

What is the size of a typical salt particle? What size of hole would required so that a continuum model of the salt flow is a reasonable assumption? (Based on Q1, p. 42 by Paterson [10].)

Solution.

Salt is not like a fluid because you can make it into a pile, whereas the surface of a resting fluid is always horizontal. However, some aspects of salt flow are similar to the flow of a fluid. A typical salt particle is approximately a cube of side \(0.5\) mm, and therefore has a volume of approximately \(10^{-10}\) m\(^3\text{.}\) We need a size of hole that admits a very large number of particles. A reasonable value of the volume \(V\) appearing in the continuum approximation might be the volume of \(3\times10^7\) salt grains (this was the number of gas or liquid molecules quoted in the notes), i.e. \(3\times10^{-3}\) m\(^3\text{,}\) which is a cube of side length approximately \(10\) cm. We need a hole that is many times this distance, perhaps a hole with a diameter of one metre or so might be reasonable! See also Remark 3.0.3.