1. Flow visualisation.

(a)

Name a few ways in which a fluid flow can be visualised (i.e. how does one produce, in an experiment, such a visualisation?)

(b)

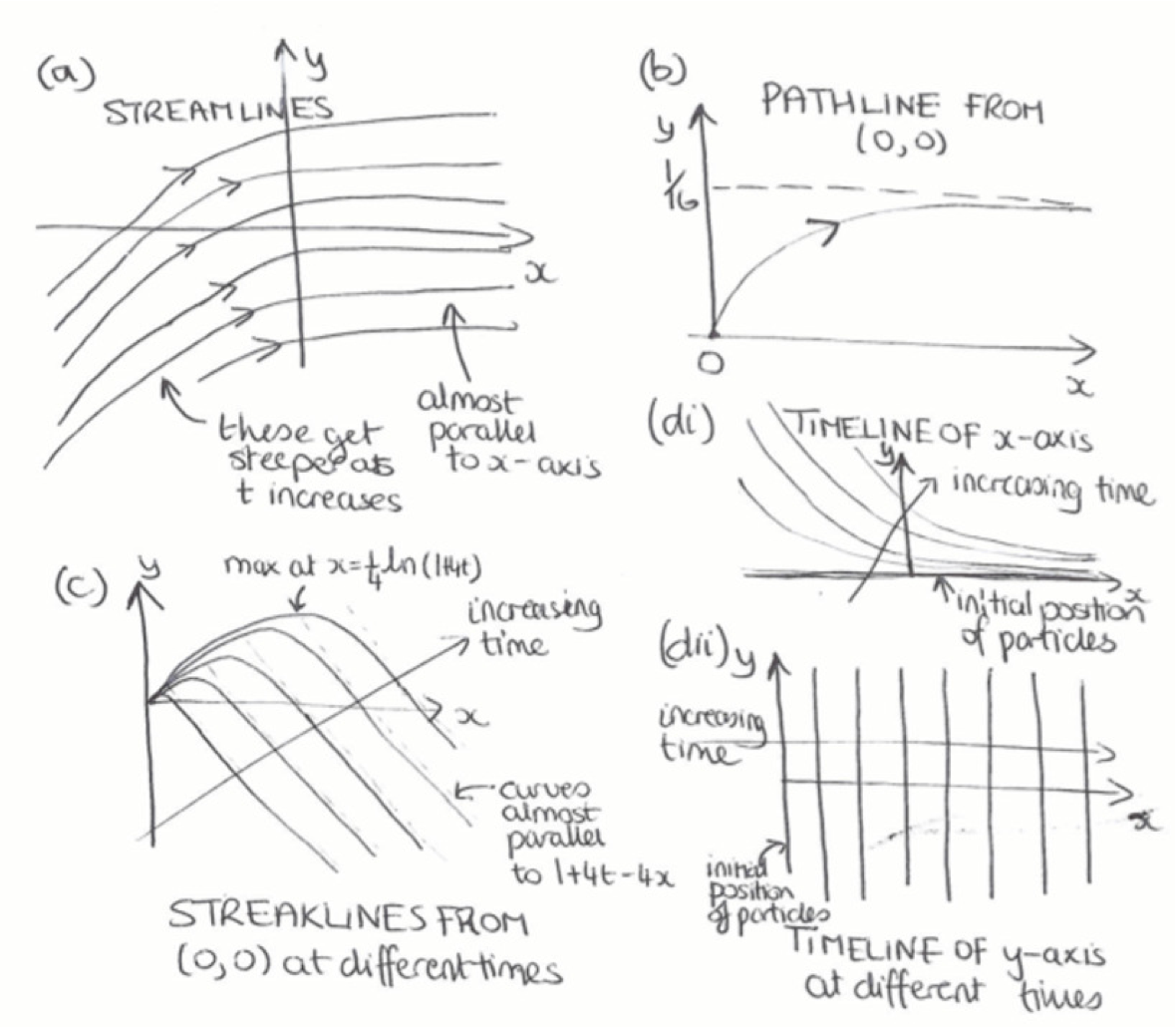

Define, in words, what pathline, streakline, timeline, and streamline means. At 6:30, the author comments that "there is no way to make a streamline visible". Discuss this point.

(c)

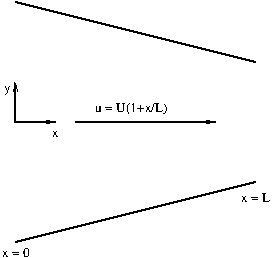

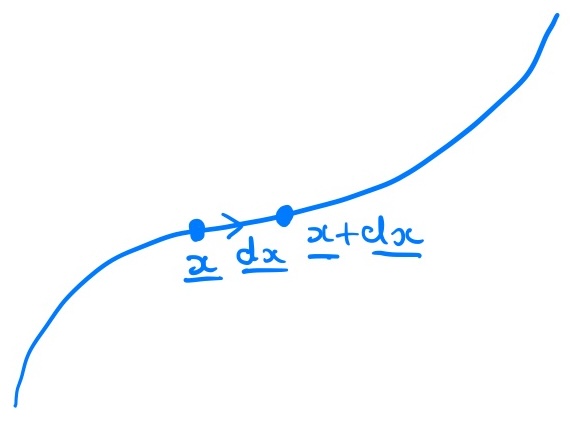

Give the example, shown in the video, where the pathline, streakline, and streamlines all coincide. Draw pictures to illustrate the concept.

(d)

Give an example, shown in the video, where the pathline, streakline, and streamlines do not coincide. Draw pictures to illustrate the concept.

(e)

In the video, an intuitive explanation is given for what it means for the velocity to be incompressible. What is this explanation? (near 8:25)